The real cost of bailing out Puerto Rico

Originally published in the Washington Examiner

A preview of this month's scramble to save Puerto Rico from a debt catastrophe played out in the fall between two familiar adversaries in a Senate office hearing room.

On the witness side of the dais was Antonio Weiss, the Treasury counselor dispatched to warn the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee that Puerto Rico faced an "economic and fiscal crisis" that, unless Congress intervened, could become a "humanitarian crisis as well."

Facing Weiss was Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator and liberal populist who, just months earlier, had blocked him from Senate confirmation to the No. 3 post in the Treasury. Warren had seized on Weiss' background as an investment banker at Lazard to paint him as the candidate of Wall Street influence, banking excess and bailouts, successfully rallying liberal opposition to his nomination.

Bailouts were again at question at the October hearing.

"During the financial crisis, when the banks were in trouble, Treasury did a lot more than just bail them out," Warren said, referring to the deals the Treasury helped broker to rescue firms like Merrill Lynch and Bear Stearns in 2008. "Treasury stretched the limits of its authority to make sure that the banks stayed afloat."

"Now the people of Puerto Rico are calling," Warren told Weiss. They are not asking for a bailout, she said, but the government should be "just as creative in coming up with solutions for Puerto Rico as it was when the big banks called for help."

Now, the fate of the 3.5 million U.S. citizens on the island territory of Puerto Rico is tied up in the bailout politics that have antagonized the electorate over the past eight years, as the exchange between Weiss and Warren demonstrated.

On the one hand is the prospect of real human suffering on the island. On the other are fears that the country hasn't learned any lessons about rewarding bad behavior and that the cycle of bailouts isn't over.

Puerto Rico's problems on their own would not be sufficient to cause the levels of apprehension and reluctance to act felt by many members of Congress, especially fiscal conservatives.

The problem, instead, is the sense that Puerto Rico might be just the first in a series of fiscal reckonings for the U.S.

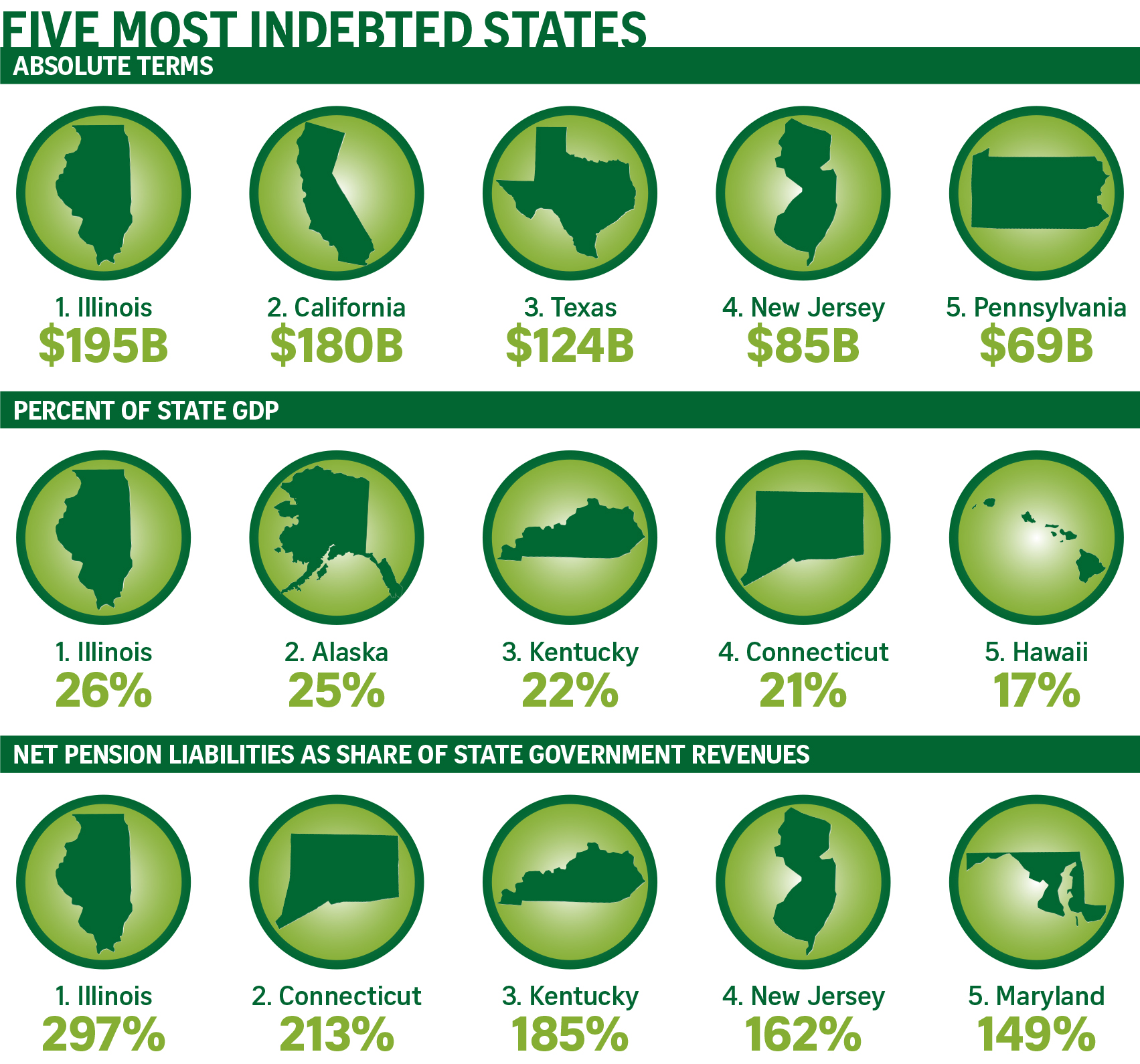

Puerto Rico's fiscal collapse, with its potentially devastating consequences for the territory's residents, is seen as the first leak to spring in the boat of states and cities that are weighed down with debt. If Puerto Rico gets a bailout, many in Congress fear, so will the others. And if Puerto Ricans suffer a hard landing, so will residents in Illinois, Connecticut, Kentucky and other people living in indebted states.

The size of the debt problem

Puerto Rico has racked up debts of about $70 billion. Compared with the island's resources, that is a huge sum: It's more than the territory's economy produces in a year, based on gross national product, and servicing it uses up one-third of the government's revenue. In comparison, the U.S. spends just 1.3 percent on interest payments. To make it worse, Puerto Rico also has $46 billion in pension liabilities backed up by only $2 billion in net assets.

Yet it's not the $70 billion that has lawmakers worried. It is the $1.3 trillion in pension liabilities the 50 states had in 2014, according to a January report from Moody's Investors Service.

One frequently cited estimate suggests that the states' shortfall is significantly larger. Stanford finance professor Joshua Rauh has found that unfunded state pension liabilities totaled roughly $3.3 trillion in 2013, when calculated assuming a more conservative rate of return on pension assets.

The $2 trillion difference in the two estimates is the result of the different ways pension liabilities can be calculated. Every time a worker is given pension benefits, the government incurs the obligation to pay him benefits that will pay out during his retirement.

To arrive at an estimate of how much those future payouts are worth today — in "present value," as it's known — the government must figure out how much money it would need to invest now to match those future sums.

The typical state plan, Rauh reported, was assuming a return of 7.75 percent, year after year. That rate, he argued, corresponds with a risky stock market investment, which is inappropriate for pension plans given that the state must pay the benefits when they are due.

Instead, the rates on risk-free Treasury securities, at 2.8 percent for the typical time frame for paying out benefits, should be the benchmark. Using that rate, total liabilities, in present value, were roughly $5.8 trillion in 2013, versus assets of just $2.5 trillion.

Most states, according to Moody's, have their pension plans under control. But some are clearly going to have trouble paying what they owe, especially the "outliers" of Illinois, Connecticut and Kentucky. Unless they take action soon to fix their problems, lawmakers fear, their citizens may face a painful reckoning, or the states may even come to the federal government looking for a bailout.

The precedent would be set if Puerto Rico receives a bailout now.

"If we do the wrong thing with Puerto Rico, I guarantee everyone and their dog will be in wanting us to do the wrong thing for them," said Sen. Orrin Hatch, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

The Utah Republican blamed Democratic state governments for the fact that it is a "very big concern" not to set a precedent for bailing out states with Puerto Rico legislation. "Almost all the blue states — in other words, Democrat states — have the usual problems because they overspend," he said. "They over-create government, and most of them are in trouble."

Day of reckoning

Not all states, or even just blue states, have pension problems. New York, for example, ranks among the states with the best-funded pensions plans.

But for the states that are in trouble, one day there will be a reckoning.

"The plain math tells you that saving the Connecticut pension system or the Illinois pension system is virtually impossible," said Steven Malanga, an expert at the conservative Manhattan Institute who has long warned of state pension problems.

The obligations that states have to employees owed pensions are not like the federal debt. Unlike Treasury bonds, the pension debts are not securities held and traded by investors. And, unlike the federal government, states are limited in their ability to issue new debt to pay income interest costs, and they cannot print money.

So for a state such as Illinois, which has $195 billion in net pension liabilities, according to Moody's, about three times the state's total annual revenue, only a few possible outcomes exist. One is that it drastically cuts back on state services to pay its bills.

"What ends up happening is the state cannibalizes itself over time," said David Skeel, a University of Pennsylvania law professor. Another is that it defaults, stiffing the public-sector workers whose pensions are at stake — a possibility made unlikely but not impossible given court rulings protecting the plans.

A third is that the state, facing a genuine disaster, taps the federal government for help.

It's that last possibility that has many in Congress, especially Republicans, worried about giving any sort of "bailout" to Puerto Rico.

"It is a concern that we should not create a circumstance that encourages reckless behavior by states," said Jeff Sessions, the fiscally conservative Republican senator from Alabama.

Illinois is the best example of the kind of recklessness that lawmakers want to avoid rewarding. For years, the state has made promises to workers without setting aside funds to make good on the promises. From 2005-09, the state misled investors about the state of its pension system, the Securities and Exchange Commission said in 2013.

Pension benefits are constitutionally protected under Illinois law. While legislators can't trim them without a constitutional amendment, they can sweeten them, as they did in 2003, worsening the state's finances.

Avoiding bailouts for states such as Illinois that have overpromised workers, however, is only part of the strategy.

Politicians on both sides of the issue would like to seize an opportunity, such as the one presented by Puerto Rico's struggles, to change laws now to try to sway the ongoing negotiations between state governments and the public-sector unions whose members are owed money.

Many Republicans seek an advantage when it comes to intense pension battles such as the one Gov. Chris Christie fought in New Jersey, a hard-fought and costly victory for Christie that nevertheless was insufficient to put the state on a firm fiscal footing.

Rep. Devin Nunes of California has proposed one such plan. He authored legislation that would require state and city pension sponsors to report to the Treasury on the funding of their plans using the methodology favored by Rauh, which assumes a lower rate of return on pension investments and would make the plans appear more indebted.

Another possibility would be to change federal law to allow states to go bankrupt. State bankruptcy would provide a way for governments to restructure their debts through an orderly process, eliminating the possibility of eviscerating state services and harming the economy.

Skeel has championed the idea of state bankruptcy to preempt bailouts for nearly as long as there have been concerns about the federal government rescuing states.

His ideas gained support among Republicans after they took control of the House in 2010, with former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich co-authoring an L.A. Times op-ed endorsing state bankruptcy laws, writing that "federal taxpayers in states that balance their budgets should not have to bail out the irresponsible, pandering politicians who cannot balance their budgets."

But then memories of the 2008 bank bailouts receded, states began to see budgets decimated by the financial crisis steadily improve and the pressure for major action on pensions abated.

Skeel acknowledges that the five years since the Bush-Gingrich op-ed are a point of evidence in favor of the idea that states can just "muddle through" their fiscal problems, surviving without significant overhauls such as state bankruptcy. But he is still worried about a possible shake-out in state pensions. "Historically, we haven't tended to plan ahead for catastrophes," he said.

And the point was never to have states actually go through bankruptcy. It was to reduce the incentives for pension holders and governments to play a game of chicken, betting that if they wait until there really is a crisis, they will get what they want, rather than compromising now. The possibility that the result in that scenario would be bankruptcy and a judge restructuring their contracts "significantly changes the bargaining dynamics in a good way," Skeel said.

In other words, workers owed years of benefits would see that they were not guaranteed to get everything they were promised, and instead could end up like retirees in Detroit whose benefits were restructured in the city's bankruptcy. That prospect would draw them to the bargaining table.

Having an endgame spelled out ahead of time — namely, bankruptcy — would eliminate some of the current standoff that has resulted in plans being underfunded.

From the point of view of a would-be reformer such as Christie, the problem is that benefits are too generous. Over time, rather than paying employees higher salaries, officials made promises to pay them in the future, in the form of higher pensions.

Now, however, when it's clearer that fulfilling those promises would require steeply higher taxes or significant benefit cuts, Christie has skipped some required pension payments. He has argued that to make the payments would be to throw good money after bad, given that the benefits cannot be paid and must be cut. In 2014, New Jersey was making just under 20 percent of what would be considered full payments.

Some analysts, however, see the problem as the other way around. Keith Brainard, research director for the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, argued that it was the failure of states to make the retirement contributions, not the level of benefits, bad investments or anything else, that led to the problems in Illinois, New Jersey and elsewhere.

Maryland is a typical example. Fully funded in 2000, its pension plans have fallen $47 billion into the red, about one and a half years' worth of state revenues. The problem, according to a report from the Maryland Public Policy Institute, is that officials have consistently overestimated how much the plans have earned.

As a result, they have been unwilling or unable to make the required payments, instead funding current needs. Larry Hogan, the new Republican governor of the state, has taken aim at such "short-term thinking," as he's called it, and this year restored a required payment that the legislature tried to divert.

Given that the root problem is that states have failed to make contributions, in Brainard's estimation, there is nothing to be gained in terms of helping those states by changing federal law. "Using Puerto Rico as a vehicle to apply something to every state is illogical," Brainard said.

Requiring them to submit reports on their pension plans to the Treasury would be an intrusion into state sovereignty, he argued, and the majority of states have taken action to shore up their finances during the economic recovery. "States are not sitting on their hands," he said. "They are recognizing that they own it."

Puerto Rico is different

Most ways you look at it, Puerto Rico's problems are markedly different from the states.

It has had its share of fiscal mismanagement, such as a power authority that gave free electricity to all cities, racking up $9 billion in debt.

But the primary reason the island has fallen into its current predicament, according to an analysis prepared last year by three former International Monetary Fund economists, is simply economic stagnation.

"The single most telling statistic in Puerto Rico is that only 40 percent of the adult population — versus 63 percent on the U.S. mainland — is employed or looking for work. The rest are economically idle or working in the gray economy," the report declared.

The report attributed the economic slump in Puerto Rico to some factors within the island's control, such as a high minimum wage and a generous welfare state, and some outside it, such as falling oil prices and the headwinds from the recession on the mainland.

But the bottom line is that Puerto Rico is economically stagnant and has lost population since 2006 and faces the prospect of a death spiral of declining public services, slowing commerce and further outmigration.

Most states, on the other hand, are economically healthy and don't face an exodus of residents. The ones that have gotten into trouble with their pensions have done so because they simply have made unsustainable promises to state workers and failed to face the reality of their situations.

The legislation

Since Puerto Rico is a territory, Congress has unique jurisdiction over the island given in the Constitution. Given those differences, Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, wants the legislation he is preparing to resolve Puerto Rico's crisis, which would create a financial control board empowered to restructure debt, to have no bearing on states.

"I don't want to have a nexus between state issues and what we're doing in Puerto Rico," said Bishop, who is chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee that has jurisdiction over territories.

That means no bailouts. It also means no legislation aimed at tipping the scale toward benefit reductions in pension negotiations, like that proposed by Nunes.

From the perspective of beleaguered Puerto Ricans, Congress must take that stance and no other. They desperately need relief and cannot afford to have it tripped up by congressional fears about a bailout or a coup against pension plans.

"The argument that the debt restructuring component of this legislation — which could potentially encompass all debt-issuing entities in Puerto Rico, while still respecting the relative rights and priorities that the creditors of such entities have under Puerto Rico law — would set a precedent for the 50 states is extraordinarily weak," said Pedro Pierluisi, who represents Puerto Ricans in Congress.

Pierluisi noted that a similar board would not be an option for a state, because Congress only has such power over territories, arguing that "this is territory-specific legislation that will help Puerto Rico and its creditors, and will not set a precedent, whether positive or negative, for the states."

Bishop's legislation also has fiscal conservative defenders, who argue that it is not a bailout but the alternative to a bailout.

Puerto Rico "already can't pay their bills," said Tom Schatz, president of of the fiscally conservative group Citizens against Government Waste. "So they have two choices: One is taxpayers write a check for some or all of those bonds ... or somebody comes in and straightens the finances."

Bishop, in an appearance on local Utah radio, made a similar point, saying his bill is the only thing preventing a bailout. "If nothing happens, there will be a total default in Puerto Rico, and I can assure you, there will be a bailout at that stage of the game," he told listeners.

Schatz compared the financial control board to boards that the federal government set up for New York City in the 1970s, when Gerald Ford famously "told" the city to "drop dead," and Washington, D.C., in the 1990s. Neither board constituted a bailout, he said, and both addressed underlying spending problems.

Yet there will be pressure to add other elements once the Puerto Rico bill leaves committee and is taken up by the Senate.

Lawmakers from badly indebted states already have tried to attach provisions to the bill. Bishop said that Illinois lawmakers, in particular, wanted help in his bill. "We're not going there," he told the Washington Examiner, adding that "we're trying to have the firewall between what we're doing and what will have an impact on the states."

Or the Obama administration could try to include fiscal sweeteners for Puerto Rico. In its recommendations for the island, it proposed boosting Medicaid spending and low-income tax credits for Puerto Ricans, outlays that many conservatives would see as bailout money and harmful incentives.

Some conservatives will object to nearly any congressional action on Puerto Rico. Heritage Action, the outside conservative group, warned in a note on Bishop's bill that it "sets a political precedent, although not a legal one. In fact, creditors will arguably expect Congress to do even more to assist distressed state governments."

Hatch declined to say exactly what would constitute a bad outcome in terms of setting precedent for states and cities. Instead, he responded, "I want to do the right thing. And that generally means getting them to live within their means and do incredibly intelligent things."