Fixing Maryland's School Monopolies

Maryland may be America in Miniature, but in at least one respect we’re big. The half-dozen public school systems from Baltimore to the DC suburbs are all among the 100 largest in the country, each enrolling more than 50,000 students. These systems have not covered themselves in glory during the pandemic, stubbornly remaining closed to in-person learning even as many public schools in other states – and many private and parochial schools in their areas – have heroically and safely done much more to mitigate their students’ learning and earning losses in the time of Covid-19.

This isn’t surprising, really. These massive enterprises, with near complete dominance of the market for elementary and secondary education within their jurisdictions, are simply doing what comes naturally for monopolies: shielded from meaningful competition, they really don’t worry much about their survival, which is assured, but look primarily to their own comfort, convenience, and safety. And these systems are actually twin monopolies, with powerful unions controlling the market for teachers and dictating work rules to the bureaucrats who steer the overall operation.

If you as a parent don’t like the way these outfits behave, you’ll need to abandon your claim to any public school tax dollars, decamp to a private school, and pay for your kids’ schooling a second time. That quite a few parents do so – and more by the day, during Covid – is, in fact, strong evidence about the public school monopolies’ deficiencies. When a price of $0 isn’t low enough to secure someone’s patronage, there might be a quality problem.

And that problem preceded and will follow the pandemic, so it deserves careful consideration as Maryland’s 2021 legislative session gets under way. Quick review: In last year’s session, we were told repeatedly that Maryland’s schools are under-achieving and that to make them “world class” we need to increase school spending by at least $32 billion over the next decade to implement the vaunted Kirwan Commission's “Blueprint for Maryland’s Future.” Though vetoed by Governor Larry Hogan, everyone expects that veto to be overridden in short order.

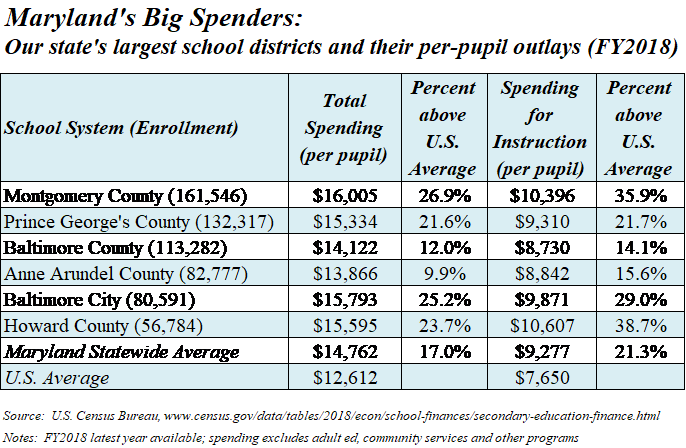

As the accompanying table illustrates, however, it’s simply not true that Maryland underfunds its public schools. Statewide, total per-pupil spending exceeds the national average by 17%. Maryland’s half-dozen largest districts out-spend the average U.S. district by as much as 27% (Montgomery) and a minimum of 10% (Anne Arundel). Its majority-minority districts, Baltimore City and Prince George’s County, respectively spend 25% and 22% more than average.

These data also illustrate the main (and perhaps only) advantage of large districts: their overhead (the costs of the bureaucracy needed to administer facilities, do necessary paperwork, etc.) is spread over more customers, so more of their budget dollars can make it into classrooms. Statewide, then, we spend 21% more than the national average on actual instruction, ranging from 14% more in Baltimore County to Howard County’s 39% advantage.

It’s true, of course, that Maryland is an affluent state. Our statewide personal income per capita is 16% above the national average, roughly mirroring our per-pupil spending level. But there’s no reason to assume that the cost of a good must be higher simply because the buyer might be well-heeled. Sure, the well-to-do might be willing to spend more to obtain a higher-quality good, but it’s important to note that many Maryland jurisdictions are not affluent (e.g., Somerset County’s personal income per capita is just 35% of Montgomery’s), so imposing the preferences of the affluent on other taxpayers seems pretty high-handed. Further, the link between school spending and school quality is more complicated than is often supposed. Sure, money can matter, but added spending generally does not yield big gains, and it’s wrong to assume it’s a necessary condition for improvement in student performance.

On at least one point, however, Kirwan’s advocates were spot on: while there are many stellar schools scattered throughout Maryland, our students’ overall performance on key metrics is lackluster. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, the "Nation's Report Card," tells the story. In 2019, Maryland 4th and 8th graders’ scores in math and reading were not significantly different from national averages. Students in Virginia, by contrast, scored significantly above national averages overall, besting Marylanders and registering higher proficiency rates in everything but 8th grade reading. And Virginia’s spending (at $12,216 per pupil) is 17% below Maryland’s. The contrast with some other high-achieving, lower-spending states is even more dramatic.

What to do? Fixing our schools does not require us to shovel more money at these twin monopolies – which, thanks to the state and local budget implosions related to Covid-19, would be a bad idea at a bad time anyway. Rather, we must inject some competition into the market for elementary and secondary education.

The foremost expert on the salutary effects of competition on public education is Stanford’s Prof. Caroline Hoxby. Prof. Hoxby has shown (twice) that competition in areas with relatively small public school districts, where people can “vote with their feet” and move in pursuit of better schools, has favorable effects on student learning all around. Ditto when public schools face meaningful competition from affordable private (often religious) schools. The less “captive” is your customer, the greater will be your efforts to produce a high-quality product. Prof. Hoxby estimates that “if every school in the nation were to face a high level of competition both from other districts and from private schools, the productivity of America’s schools, in terms of students’ level of learning at a given level of spending, would be 28 percent higher than it is now [emphasis added].”

Here in Maryland, with its big and sprawling school districts, it’s not strictly necessary to “break up” these monopolies by redrawing district lines – even if that were politically feasible. What is necessary is modifying some regulations within districts so that parents and students have more choices – and the public schools have to compete for their patronage. The way to do that is with more liberal public charter school laws (approving charter applications more easily and funding them more fully) and with voucher programs targeted to poorer families otherwise unable to afford private schools.

Hoxby finds that such programs do not simply benefit the students attending charters or receiving vouchers. Those “left behind” also benefit as the publics step up their game dramatically in order to compete for students and maintain their funding. For example, “in Milwaukee, schools facing more competition from vouchers improved at rates faster than schools facing little or no competition from vouchers. Public schools in Michigan and Arizona began improving at faster rates after they lost significant shares of their enrollment to charter schools.” The same was true in Chicago and New York.

To realize similar gains in the quality of Maryland schools, however, major political obstacles must be overcome. The state’s Education Industry Complex is its most powerful special interest group; it rewards its minions in the legislature – many of whom were once themselves teachers or members of the ed bureaucracy – with generous campaign contributions and large blocs of votes if they support the status quo and spanks them for any deviation from the party line.

If there’s any hope that we might hurdle these obstacles, it comes from the rising dissatisfaction of parents who have seen, as the pandemic grinds on and their children are ill-served by these twin monopolies, that they need school choice more than the schools need more Kirwan-mandated money. As this legislative session gets going, let’s hope they make their feelings known.

Stephen J.K. Walters (email: swalters@mdpolicy.org) is chief economist at the Maryland Public Policy Institute and the author of Boom Towns: Restoring the Urban American Dream.