(photo credit: AREP, https://americanrepartners.com/page/214/one-south-street)

No, Baltimore, All Is Not Well

We Baltimoreans do not like bad news. We often take it personally; as criticism. Such defensiveness is a bad reflex; it can prevent us from solving real problems. If our doctor diagnosed a broken arm, we know it would be silly to say “Doc, you’re too negative – let’s talk about my excellent cholesterol numbers.” In the policy sphere, though, we do that sort of deflection and denial all the time.

Let’s start where the buck stops – in the mayor’s office. In his letter selling his FY2024 budget, for example, Brandon Scott told this whopper: “Make no mistake – our city is growing, as evidenced by strong economic development.”

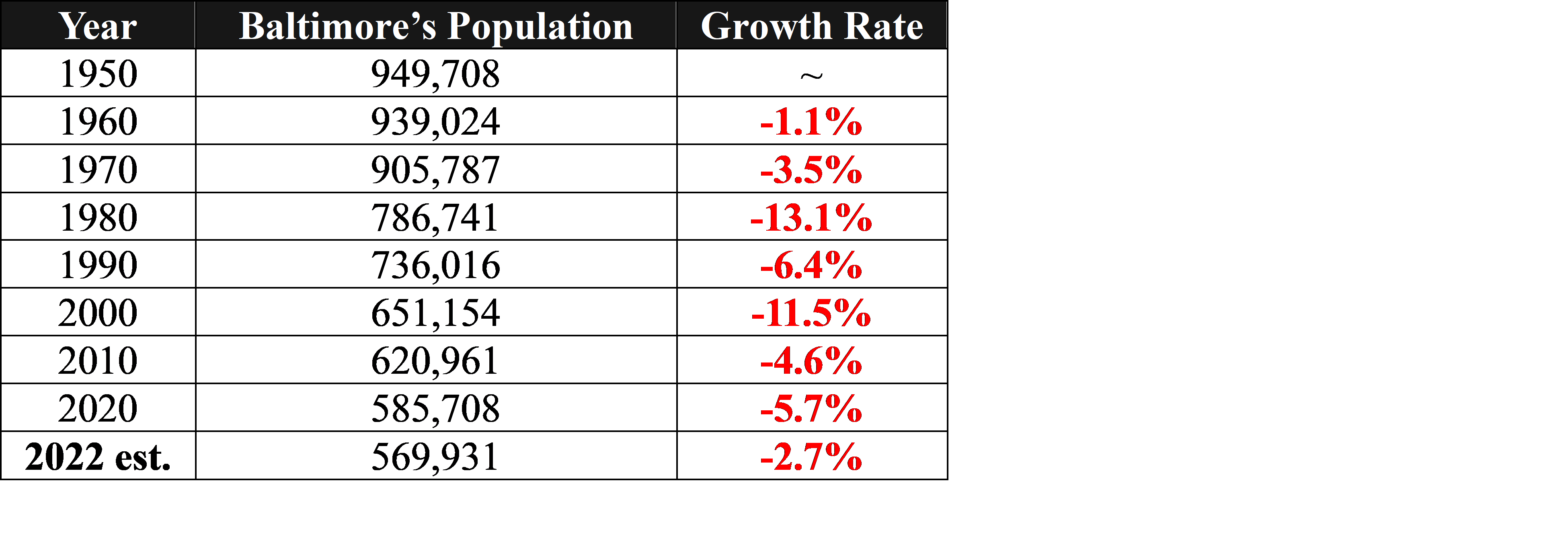

The best evidence that a city is growing, of course, is the Census Bureau’s count of the number of people willing to live there. By that measure, Baltimore is now in its eighth consecutive decade of shrinkage. It’s worth posting the historic numbers because some might think our flight problem is a result of the recent surge in homicides or declines in school performance. Such factors doubtless play some role, but the trend has been going on so long – and when crime was low as well as high, and schools performed better than today – that we should understand there are deeper, more systemic forces at work here.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the recent news is especially bad. Just between the April 2020 Census count and the July 2022 estimate, the city lost almost 16,000 residents – which works out to about 600 per month. In Mr. Scott’s budget are many expenditure items that do not shrink with population: pension costs, maintenance of crucial infrastructure, and much more. With fewer taxpayers and huge fixed costs, fiscal disaster looms if we don’t reverse flight. We won’t solve that problem if we ignore it.

But maybe we should cut Mayor Scott some slack: there’s a spin control gene in every politician’s DNA. We’d hope for better, though, from those charged with covering the city’s politicians and assessing the consequences of their policies. Too often we just get… more spin.

Consider, for example, the recent news that a downtown office building – One South Street – worth $66 million in 2015 just sold for $24 million. Of course, there are many reasons for this catastrophic $42 million markdown (and for a similar loss on a nearby property). The “Covid Effect” and remote work, downtown crime and grime, high property and business taxes that have made suburban locations more attractive for those seven-plus decades of shrinkage, and probably a few more.

It’s reasonable to consider these possibilities, but what’s irresponsible is to focus on one of them (Covid fallout) and proclaim that this is “not a crisis.” Nevertheless, The Sun’s editorial writers did exactly that.

In fact, Baltimore’s recent distress sales are like a dead canary in a coal mine. They do signal crisis; they debunk the mayor’s claim that Baltimore is benefiting from “strong economic development.” Over the same period that One South Street lost 64% of its value, commercial real estate prices nationally rose 46%. Covid’s effects elsewhere have been modest: since peaking in the fourth quarter of 2021, commercial real estate prices have fallen just 2% nationwide.

And while overstating the influence of Covid, The Sun editorialists downplay other factors:

"...[R]emember that while those big downtown buildings may have lost value, residential property values do not appear to have suffered. Indeed, they appear to be rising. Collectively those homes and condos represent about 56% of the city’s assessed property. Meanwhile the city isn’t as property tax dependent as some other jurisdictions. According to the comptroller’s calculations, the collections are about $1,744 per capita, which is just sixth highest in the state."

Note first that if 44% of the property tax base is commercial and those values are declining, that’s a major problem. Second, the modest growth in home prices here lags growth in other cities by a large margin, even in our most desirable neighborhoods.

Finally, focusing on the "per capita property tax" rather than the city’s tax rate (twice that of any Maryland county) is disingenuous spin. But even that metric signals another big problem: the city's per capita income is $34,378, which is 25% below the state average of $45,915 and ranks fourth lowest in the state. In short, even by their chosen (artificial) measure, the city’s property tax burden is not just excessive but highly regressive.

The good news is that the shrinkage in the city’s tax base and population can be reversed with a dose of sensible policy: a competitive property tax rate to encourage rather than repel the kind of commercial and residential investment that is the lifeblood of an urban economy. MPPI has been writing about the need for tax reform for years; the analysis and prescriptions for change are available here, here, and here. Baltimore is eminently fixable. But not if we keep pretending all is well.

Stephen J.K. Walters is Chief Economist at the Maryland Public Policy Institute and author of Boom Towns: Restoring the Urban American Dream.