Maryland pays more than $320 million in fees to manage pension funds. What does the state get in return?

Originally published in the Washington Post

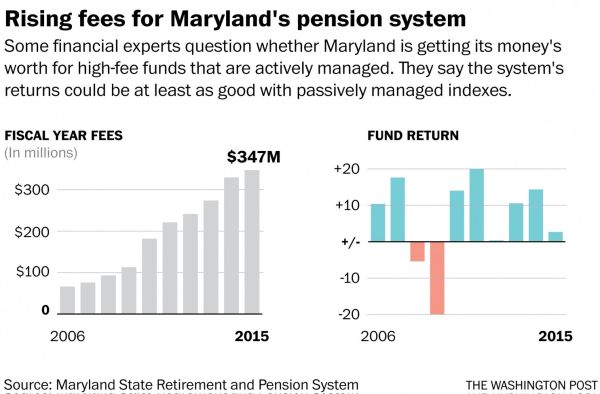

Maryland’s public pension system pays more than $320 million in fees each year to professional fund managers who tout their ability to beat the market with smart investments.

But some financial experts question whether those fees really pay off for the more than 382,000 active and former state employees who participate in the retirement plan, including teachers, state police and judges.

The state’s pension portfolio is on track to fall below the program’s modest goal of a 0.51 percent return on investments for fiscal 2016, which ends June 30. As of April 30, the plan had earned a mere 0.12 percent.

If the fund continues to underperform through June, it could bolster an argument that Washington, D.C.-based financial analyst Jeff Hooke has made for at least the past five years — and that several other states have recently adopted: Public pension systems should bid farewell to high-cost financial wizards and shift more money into passively managed index funds such as those that mimic the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index.

“Their sales pitch is that they can do better than index funds — that they can beat the stock market and bond market and be less risky,” Hooke said of fund managers. “You look at the facts, and they’re not beating the indexes. They’re not picking the right stocks and bonds, yet they’re charging much more for comparable investments. . . . It’s like a triumph of marketing over common sense.”

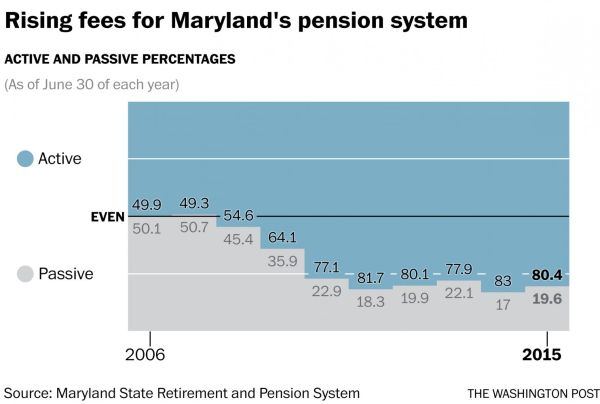

Hooke said in a report this year for the conservative-leaning Maryland Public Policy Institute that fund managers don’t do much for their fees besides “just copying a well-known benchmark, like the S&P 500.” He noted that the state’s fees have increased drastically in recent years — as Maryland shifted away from passively managed investments in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis — and that the fund’s actively managed portfolio has underperformed.

Maryland pension officials say the safest bet is to diversify the state’s portfolio with a mix of actively and passively managed investments. Andrew C. Palmer, chief investment officer for Maryland’s State Retirement Agency, said actively managed funds can be more stable than low-fee indexes, which tend to experience dramatic dips and spikes. When investments do poorly, pension participants sometimes have to contribute more money to the system to keep it healthy.

“We try to minimize contribution volatility to the extent that we can,” Palmer said.

Hooke analyzed data from 33 state pension systems that use the same fiscal year as Maryland, finding that those programs spent $6 billion on asset-management fees in 2014 and that the 10 states with the highest fee ratios — Maryland ranked fourth — achieved lower return rates than those that spent the least.

Palmer acknowledged that some actively managed investments have produced low returns recently, but he said indexes only appear to be the better option because they experienced some of their largest gains on record during the past five years.

“Using that period, it’s going to be hard for any portfolio without a high concentration of U.S. stocks to look good,” he said. “Any type of alternative investment is going to be disadvantaged.”

In response to Hooke’s report, Palmer and State Retirement Agency chief R. Dean Kenderdine published a four-page memo last week saying that they are “confident that hedge funds serve an important risk-reducing role in the total portfolio and their performance should improve.” Hedge funds are one of the most common actively managed investments.

Since 2007, Maryland’s investment fees have more than quadrupled, shooting up from $76 million in 2007 to $347 million in 2015. The jump reflects the state’s increased use of actively managed funds, which now make up 80.4 percent of its portfolio, compared with about 49 percent in 2007.

Maryland’s average annual return for the five-year period ended in 2015 was 9.36 percent. By comparison, the annual average return for the five-year period ended in 2007 was 11.3 percent.

Maryland Treasurer Nancy K. Kopp (D) said the pension board, which she chairs, strives to create a “diversified long-term investment portfolio that will provide enough to pay benefits over a long period of time and buffer us from volatile markets.”

Kopp added that Hooke’s 2016 report “overly simplifies the task of the Board in its duty to set an appropriate asset-allocation policy.”

Prominent investors such as Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway’s chairman and chief executive, are encouraging investors to move away from high fees and active management. Some states and municipalities are doing just that.

Nevada has transitioned almost entirely to passive management since 2014, indexing 100 percent of its mutual-fund and tradable-securities portfolios. California last year began cutting ties with half of its outside fund managers to make its portfolio less complex and expensive, and Illinois has slashed its use of hedge funds by 70 percent while replacing about 40 percent of its high-cost investment managers with index-based portfolios.

New York City’s comptroller last year determined that many of the city’s actively managed funds were not meeting their targets after accounting for fees. In April, the city’s pension board voted to pull out of its $1.5 billion hedge-fund portfolio after deciding that the assets didn’t perform well enough to justify their fees.

Other states have found ways to continue using actively managed investments without sending so much fee money to outside managers. In 2014, North Carolina’s treasurer proposed moving some of the work in-house, and the legislature responded by funding 10 new investment positions and allowing flexibility to pay market-rate salaries for those employees.

Maryland Del. Brooke E. Lierman (D-Baltimore), a member of the House pension-oversight subcommittee, said she and other members of the panel will take a hard look at investment fees this fall, when the Department of Legislative Services briefs lawmakers on the state’s fiscal 2016 returns.

“I don’t want to pay exorbitant fees or unnecessary fees,” Lierman said. “It’s something the oversight committee has been paying attention to and talking to the treasurer about. I want to hear the full stories before I make any judgment.”