Repackaging a gross hotel deal in Frederick

The nine-year-old saga of an $84 million government-sponsored downtown hotel and conference center complex in Frederick took some new turns in the first half of the year.

One turn: After Gov. Larry Hogan had zeroed out the state contribution to the project in his budget, Sen. Ron Young (D–Frederick) pulled off a deal with the state Senate leadership to get authorization for $16 million in state funds for the controversial project. That money still has to make it through the Board of Public Works, comprising Maryland’s governor, treasurer and comptroller. But it was a breakthrough for the complex’s promoters that the money was appropriated over the governor’s wishes and opposition from the majority of the eight-person Frederick County delegation to Annapolis.

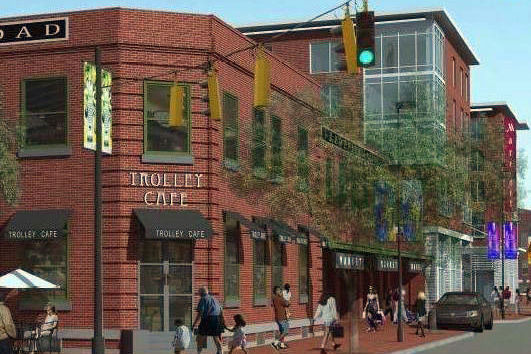

A second turn came a few weeks later, when Frederick City Mayor Randy McClement announced major changes to the project. New plans and models were put on display May 18th that lopped a story off what was initially proposed to be a five-story building, reducing the room count from 207 to 183. The size of the conference center also shrunk from 24,000 to 20,000 square feet. These moves were aimed at local residents concerned by the original proposed size of the hotel, and also the historic preservation regulators who have yet to adjudicate what is going to be permitted in Frederick’s Historic District. Parking in a basement garage underneath was also expanded from about 105 vehicles to 167, also to alleviate nearby residents’ concerns and satisfy the city’s planning commission.

The most dramatic turn, however, was the claim that the complex’s private developer, Plamondon Hospitality Partners, supposedly would now fully fund the conference center attached to the hotel. This seemed to be a huge concession to critics of the project who had objected for years to public money being used to build meeting space that would be, in effect, gifted to the developer to operate as part of its business. For years, promoters of the project had said that Frederick had to have a modern conference center downtown but public money was needed for the project because it could not be expected to pay for itself.

On its face, this turn-around was a triumph for critics, or at least a major concession to their criticisms. A more cynical—and probably accurate—interpretation was that it was just a juggling of the books to suggest the project would be privately funded, but to get Governor Hogan and the Board of Public Works to release the appropriated money. The Governor has said it’s wrong to fund a conference center for a new hotel when a competitor, just a mile away, is prepared to build a conference center with its own money.

By now it is nearly two months since the announcements of the new plans and the hotel developer’s willingness to fund the conference center. And, supporting the “book-juggling” interpretation, city officials won’t explain how these changes affect the project’s budget. Regular inquiries and Public Information Act requests have revealed that the deal between public officials and the developer that had the developer ostensibly funding the entire cost of the conference center (put at $8.3 million) was done without any records at all. No memoranda, no records of conversation, no letters exchanged, no emails—nothing. The word was that it was a “handshake deal.”

And it has been followed by weeks of obfuscation over precisely what the “new deal” is. If the developer is taking over $8.3 million in expenses, then would expect that amount would be subtracted from the $31 million in public funds originally requested from the state, county, and city governments. But so far, there’s no indication of that subtraction; the city is making no move to reduce its demands on its “partners” in county government or at the state level. The city can’t or won’t produce a revised project capital budget showing up-to-date sources and uses of funds.

It thus seems that the original public/private split (63% private, 37% public) of the project’s cost hasn’t materially changed in the mysterious new deal. Apparently the public sector is taking on new financing responsibilities whose cost more or less matches the $8.3 million supposedly saved on the conference center. The main suspect for the new public spending is the cost of the enlarged basement parking garage, which the city will finance. At 105 parking spaces, it was estimated to cost $9.5 million or $92,000 per parking space. At the newly announced 167 spaces and the same per parking-space cost, the parking garage will now cost around $15.3 million.

Realize that $92,000 per parking space is very expensive! The leading academic on parking, Donald Shoup of UCLA, cites a survey of 12 cities’ underground parking garage costs showing construction costs per parking space as ranging between $26k in Denver and $48k in Honolulu, with the average of the 12 major cities as $34k. Washington DC costs are $29k, New York is $35k, Chicago $36k. So why would Frederick spaces be so much more expensive?

Maybe costs have gone up 10% since the 2014 survey, making average big-city underground parking costs now a national average of $37,400 per space. On that basis the 167 space underground garage in downtown Frederick should cost around $6.3 million. How can Frederick spend $15.3 million, or $9 million more than average big-city costs on this parking garage, which they now say is independent of the hotel?

The answer seems to be that the city, by funding a large basement parking garage, is taking on the costs of building the foundations and the first floor deck for the private hotel complex. At its new, larger size the garage provides columns and a deck large enough to support the great bulk of the hotel complex above. The site of the project has a history going back to the 18th century of tanning and other dirty manufacturing, all in a creek floodplain. If the city is taking over the foundation, then the private developer is relieved of the financial and engineering risks of deep-pile foundations, excavation, and basement walls, and possible contamination clean-up. That’s a great deal for the developer in return for taking over the funding for a conference center in its own facility.

The Frederick City administration is getting into dicey legal territory now. In December 2015 the Board of Aldermen, the city’s legislative arm, held public presentations and hearings after which they voted to endorse a contract or “deal” with the developer in a very detailed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) spelling out the specifications for the hotel complex and the rights and responsibilities of the various parties. It was that MOU-based project that the city administration has hawked to Frederick County and more importantly to various state agencies and to the General Assembly. But that same project was announced as defunct on May 18th without any explanation of what takes its place, without making an amendment to the December 2015 MOU to the City Board of Aldermen, and without any notification to the county and state “partners” of the city administration’s maneuver.

The project is being cosmetically repackaged in an effort to make it politically more acceptable. It still represents a huge gift of public money to a private developer.

This project has been poisoning the investment climate in Frederick for almost a decade now, denying the city of the benefits of normal investor-funded hotels downtown. Annapolis should be Frederick’s model with about eight investor-financed hotels downtown offering an array of lodging choices and price points for visitors.

Peter Samuel is and adjunct fellow at the Maryland Public Policy Institute, and a journalist based in Frederick who has been following this project closely for several years.